Kerry’s Meeting With Communists Broke U.S. Law

Kerry’s Meeting With Communists Broke U.S. Law

Marc Morano, CNSNews.com Thursday, May 20, 2004

The 1970 meeting that John Kerry conducted with North Vietnamese communists violated U.S. law, according to an author and researcher who has studied the issue.

Kerry met with representatives from “both delegations” of the Vietnamese in Paris in 1970, according to Kerry’s own testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on April 22, 1971. But Kerry’s meetings with the Vietnamese delegations were in direct violation of laws forbidding private citizens from negotiating with foreign powers, according to researcher and author Jerry Corsi, who began studying the anti-war movement in the early 1970s.

According to Corsi, Kerry violated U.S. code 18 U.S.C. 953. “A U.S. citizen cannot go abroad and negotiate with a foreign power,” Corsi told CNSNews.com.

By Kerry’s own admission, he met in 1970 with delegations from the North Vietnamese communist government and discussed how the Vietnam Warshould be stopped.

Kerry explained to Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman J. William Fulbright in a question-and-answer session on Capitol Hill a year after his Paris meetings that the war needed to be stopped “immediately and unilaterally.” Then Kerry added: “I have been to Paris. I have talked with both delegations at the peace talks, that is to say the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the Provisional Revolutionary Government.”

However, both of the delegations to which Kerry referred were communist. Neither included the U.S. allied, South Vietnamese or any members of the U.S. delegation. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam was the government of the North Vietnamese communists, and the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PVR) was an arm of the North Vietnamese government that included the Vietcong.

Kerry did meet face-to-face with the PVR’s negotiator Madam Nguyen Thi Binh, according to his presidential campaign spokesman Michael Meehan. Madam Binh’s peace plan was being proposed by the North Vietnamese communists as a way to bring a quick end to the war.

But Corsi alleged that Kerry’s meeting with Madam Binh and the government of North Vietnam was a direct violation of U.S. law.

“In [Kerry’s] first meeting in 1970, meeting with Madam Binh, Kerry was still a naval reservist – not only a U.S. citizen, but a naval reservist – stepping outside the boundaries to meet with one of the principle figures of our enemy in Vietnam, Madam Binh, and the Viet Cong at the same time. [Former Nixon administration aide Henry] Kissinger was trying to negotiate with them formally,” Corsi told CNSNews.com.

Corsi’s recent essay, titled “Kerry and the Paris Peace Talks,” published on wintersoldier.com, details Kerry’s meetings and the possible violations of U.S. law.

Corsi also asserted that by 1971, Kerry might have violated another law by completely adopting the rhetoric and objectives of the North Vietnamese communists.

Definition of Treason

“Article three: Section three [of the U.S. Constitution], which defines treason, says you cannot give support to the enemy in time of war, and here you have Kerry giving a press conference in Washington on July 22, 1971 (a year after his meeting with the communist delegations in Paris) advocating the North Vietnamese peace plan and saying that is what President Nixonought to accept,” Corsi explained.

“If Madam Binh had been there herself at that press conference, she would have said exactly what Kerry said. The only difference is she would not have done it with a Boston accent,” Corsi said.

The 7 Point Plan created by the North Vietnamese communists was nothing more than a “surrender” for the U.S., according to Corsi.

“You don’t advocate that [7 point] plan unless you are on the communist side. It was seen as surrender. [The U.S.] would have had to pay reparations and agree that we essentially lost the war,” Corsi said.

Communist Shill

“Kerry was openly advocating that the communist position was correct and that we were wrong. He had become a spokesman for the communist party,” Corsi added.

Kerry’s presidential campaign did not return repeated phone calls seeking comment, but campaign spokesman Michael Meehan told the Boston Globe in March, “Kerry had no role whatsoever in the Paris peace talks or negotiations.

“He did not engage in any negotiations and did not attend any session of the talks,” Meehan added.

‘From Their Point of View’

Kerry “went to Paris on a private trip, where he had one brief meeting with Madam Binh and others. In an effort to find facts, he learned that status of the peace talks from their point of view and about any progress in resolving the conflict, particularly as it related to the fate of the POWs,” Meehan added. Kerry was reportedly on his honeymoon with his first wife, Julia Thorne, when he met with the communist delegations.

But Corsi does not accept the Kerry campaign’s explanation.

“Meehan made it sound like they were just there on a honeymoon and they got a meeting with Madam Bin, but not every American honeymooner got to meet with Madam Binh. Unless you had a political objective and they identified you as somebody as sympathetic, you were not going to get invited to a meeting with Madam Binh,” Corsi said.

“Kerry has skirted with the issue of violating these laws,” Corsi added. Sen. Kerry’s presidential campaign is “trying to fudge on the issue because they don’t want to come clean on it entirely.”

On Sept. 21, 2004, the Swift Boat Veterans for the Truth introduced a TV ad titled, “Friends,” with the message that “John Kerry Secretly Met Enemy Leaders” during the Vietnam War, in 1970, while he was yet in the Naval Reserves.

Ads by Google

Heavenly TriviaYou Think You Know The Bible Well? Test Yourself With Our Trivia Game http://www.BibleTriviaTime.com

CDL A Drivers WantedWe Need Refrigerated Drivers Today. Truck Driver Positions. Apply Now! DriveForPrime.com

The Kerry immediate response team jumped into action, charging rather characteristically that the Swift Vets were lying. John Kerry, his surrogates maintained, did not meet “secretly” with Vietnamese communist negotiators to the Paris Peace talks – he openly told Sen. Fulbright’s committee in April 1971 that he had traveled to Paris and met with “both sides” to the Paris Peace talks.

Since he told the Fulbright Committee about his meeting, it could not be “secret,” the spokespersons for the campaign maintained. Besides, since he met with “both sides,” implying that one of the sides had to be ours, how could the trip have been anything else other than a fact-finding trip? Besides, many anti-war radicals were in Paris in 1970 and 1971 meeting with the Vietnamese communists, why wouldn’t John Kerry have done the same?

Dissecting “Kerry-speak” takes some doing. First, the meeting was secret. Only in March of this year, did Michael Meehan, one of Kerry’s top spokespersons, finally admit to the Boston Globe that Kerry did actually meet with Madame Binh, the top Viet Cong negotiator to the Paris Peace talks. Even today, we do not know how Kerry arranged the meeting, where it was held, how long it lasted, or what precisely Kerry and Madame Binh discussed. These details remain hidden.

All we know for sure is that on July 22, 1971, John Kerry held a press conference in Washington, D.C., where – surrounded by POW families – he called upon President Nixon to accept Madame Binh’s peace proposal, a peace proposal that called for the United States to set a date for military withdrawal and pay reparations – in effect, to surrender – all this to induce the Vietnamese communists to set a date for the release of our POWs.

Madame Nguyen Thi Binh is not someone familiar to most Americans today. Yet, in 1970, she was virtually the “Dragon Lady” of the Viet Cong. Madame Binh was a close associate of Ho Chi Minh. She was a teacher who achieved distinction in North Vietnam for her time in the captivity of the French during the war before the French withdrew and we arrived to take up the fight.

Madame Binh was beautiful and highly intelligent. Just before John Kerry came on the scene, Ho Chi Minh had dispatched one of his closest associates, Lo Duc Tho, to Paris in order to perfect the 7-point peace plan Madame Binh would advance. Lo Duc Tho was one of the original founders of the Communist Party of Indochina and one of the North Vietnamese communist’s chief strategists.

Lo Duc Tho and Madame Binh crafted a clever plan designed to undermine the formal peace negotiations being undertaken on behalf of the United States government by Richard Nixon’s appointed team of negotiators headed by Henry Kissinger. The point of Madame Binh’s 7-point peace proposal was that the only barrier to our getting our POWs back was our own unwillingness to set a date for withdrawal. The Vietnamese communists wanted the world to perceive that the only unreasonable party in this conflict was the USA, not the Vietnamese communists. In other words, we ourselves in our refusal to set a date to end the war were the sole reason our POWs were not coming home.

When John Kerry appeared on the scene, a handsome and decorated war veteran turned anti-war activist, he was the perfect candidate to carry the communist message back to the United States. Judged by the outcome, Kerry’s trip to Paris no simple “fact-finding mission.” The evidence is that Kerry – while still in the Naval Reserves – inserted himself into a complex negotiation with the result that he advanced the communist side to the detriment of our official negotiating position.

The historical record is that when he returned home he held a public press conference to endorse Madame Binh’s proposal. From Paris where Kerry received the communist message, to Washington, D.C., where he mouthed that message, Kerry became Lo Duc Tho and Madame Binh’s surrogate spokesperson.

Nor did the “both sides” include the United States delegation to the Paris Peace talks. There is no historical evidence that would support a Kerry contention that he met with anyone else other than the Viet Cong, officially known as the Provisional Revolutionary Government, of whom Madame Binh was the foreign minister, and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the official name of North Vietnam’s communist government, of which Lo Duc Tho was a member. There were two Vietnamese communist parties to the Paris Peace talks – these are the “both sides” with whom Kerry met.

When John Kerry in his street-theater military fatigues sat before Sen. Fulbright’s Foreign Relations Committee, he was there to deliver the enemy’s message. America, so Kerry maintained, was fighting an immoral war. We were a colonial power inserting ourselves on the wrong side of a civil war, in support of a puppet regime not supported by the people of Vietnam. The American military, so Kerry argued, were committing atrocities on a daily basis, atrocities which were approved up and down the entire chain of command – the army of Ghengis Khan.

Kerry’s 1971 message to the U.S. Senate was communist propaganda, pure and simple. Yet even today, in 2004, while running for president, Kerry refuses to apologize to his fellow veterans. Instead, he and his campaign supporters still seize upon every story of a war crime in Vietnam in a desperate attempt to prove that atrocities were not isolated illegal acts, but everyday occurrences, a natural outcome of officially sanctioned rules of engagement.

John Kerry ‘Negotiated’ With The Viet Cong

Lest we forget John Kerry’s attitude towards our troops in time of war. As we have mentioned elsewhere, John Kerry met with the Vietcong and North Vietnamese in Paris in May of 1970.

Kerry was so proud of (illegally) negotiating with our country’s enemies, he brought it up in his testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in April 22, 1971:

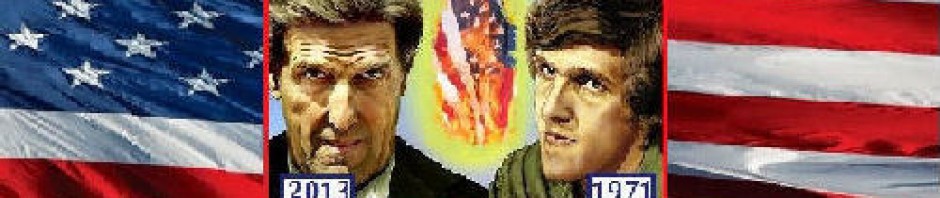

First peace meeting between Kerry’s group the Vietnam Veterans Against War and the NLF, Paris, 1971

LEGISLATIVE PROPOSALS RELATING TO THE WAR IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

THURSDAY, APRIL 22, 1971

UNITED STATES SENATE;

COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS,

Washington, D.C.

The committee met, pursuant to notice, at 11:05 a.m., in Room 4221, New Senate Office Building, Senator J. W. Fulbright (Chairman) presiding.

Present: Senators Fulbright, Symington, Pell, Aiken, Case, and Javits.

The CHAIRMAN. Do you support or do you have any particular views about any one of them you wish to give the committee?

Mr. KERRY. My feeling, Senator, is undoubtedly this Congress, and I don’t mean to sound pessimistic, but I do not believe that this Congress will, in fact, end the war as we would like to, which is immediately and unilaterally and, therefore, if I were to speak I would say we would set a date and the date obviously would be the earliest possible date. But I would like to say, in answering that, that I do not believe it is necessary to stall any longer. I have been to Paris. I have talked with both delegations at the peace talks, that is to say the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the Provisional Revolutionary Government and of all eight of Madam Binh’s points it has been stated time and time again, and was stated by Senator Vance Hartke when he returned from Paris, and it has been stated by many other officials of this Government, if the United States were to set a date for withdrawal the prisoners of war would be returned…

In fact, in his same testimony, Mr. Kerry admitted that his actions were questionable, to put it mildly:

Mr. KERRY. Mr. Chairman, I realize that full well as a study of political science. I realize that we cannot negotiate treaties and I realize that even my visits in Paris, precedents had been set by Senator McCarthy and others, in a sense are on the borderline of private individuals negotiating, et cetera. I understand these things…

Indeed, Kerry had gone to meet with the North Vietnamese and Vietcong delegation in Paris during his honeymoon, a full year before the rest of his Vietnam Veterans Against War (VVAW) went there for further negotiations.

From the Boston Globe:

Kerry spoke of meeting negotiators on Vietnam

By Michael Kranish and Patrick Healy, Globe Staff, 3/25/2004

WASHINGTON — In a question-and-answer session before a Senate committee in 1971, John F. Kerry, who was a leading antiwar activist at the time, asserted that 200,000 Vietnamese per year were being “murdered by the United States of America” and said he had gone to Paris and “talked with both delegations at the peace talks” and met with communist representatives.

Kerry, now the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee, yesterday confirmed through a spokesman that he did go to Paris and talked privately with a leading communist representative. But the spokesman played down the extent of Kerry’s role and said Kerry did not engage in negotiations…

Kerry’s speech before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on April 22, 1971, is one of the best-known moments of his life when he was involved in Vietnam Veterans Against the War. In that speech, Kerry asked: “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?”

But the follow-up session of questions and answers, made public at the time in the official proceedings of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, has received little mainstream notice until now.

When Kerry was asked by committee chairman Senator J. William Fulbright how he proposed to end the war, the former Navy lieutenant said it should be ended immediately and mentioned his involvement in peace talks in Paris.

“I have been to Paris,” Kerry said. “I have talked with both delegations at the peace talks, that is to say the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the Provisional Revolutionary Government and of all eight of Madam Binh’s points . . . .”

The latter was a reference to a communist group based in South Vietnam. Historian Stanley Karnow, author of “Vietnam: A History,” described the Provisional Revolutionary Government as “an arm of the North Vietnamese government.” Madam Nguyen Thi Binh was a leader of the group and had a list of peace-talk points, including the suggestion that US prisoners of war would be released when American forces withdrew.

After their May 1970 marriage, Kerry traveled to Paris with his wife, Julia Thorne, on a private trip, Meehan said. Kerry did not go to Paris with the intention of meeting with participants in the peace talks or involving himself in the negotiations, Meehan added, saying that while there Kerry had his brief meeting with Binh, which included members of both delegations to the peace talks.

Julia Thorne and John Kerry in 1972

Note that in Kerry’s 1971 Senate testimony, after he finished his prepared statement, he was asked for his advice on how to end the war. What he suggested was that the US accept the terms of the Vietcong as presented to him by their Foreign Minister Madam Binh. He reiterated this several times over the rest of his lengthy comments to the Senate.

Indeed, Kerry was a major propagandist for the so-called “People’s Peace Treaty.” His group, the VVAW had signed it–in a ceremony–and Kerry promoted it at every opportunity. This “treaty” incorporated every one of the Vietcong’s points.

Here are all eight of Madam Binh’s points (Binh was the Foreign Minister for the Vietcong) spelled out in the “People’s Peace Treaty” that Kerry and the VVAW and signed, and which they demanded the US sign with North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front:

Joint Treaty of Peace Between the People of The United States of America, South Vietnam and North Vietnam

Preamble

Be it known that the American people and the Vietnamese people are not enemies. The war is carried out in the names of the people of the United States and South Vietnam, but without our consent. It destroys the land and people of Vietnam. It drains America of its resources, its youth, and its honor.

We hereby agree to end the war on the following terms, so that both peoples can live under the joy of independence and can devote themselves to building a society based on human equality and respect for the earth. In rejecting the war we also reject all forms of racism and discrimination against people based on color, class, sex, national origin, and ethnic grouping which form the basis of the war policies, past and present, of the United States government.

Terms of Peace Treaty

1. The Americans agree to immediate and total withdrawal from Vietnam, and publicly to set the date by which all U.S. military forces will be removed.

2. The Vietnamese pledge that as soon as the U. S. government publicly sets a date for total withdrawal: they will enter discussions to secure the release of all American prisoners, including pilots captured while bombing North Vietnam.

3. There will be an immediate cease-fire between U. S. forces and those led by the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam.

4. They will enter discussions on the procedures to guarantee the safety of all withdrawing troops.

5. The Americans pledge to end the imposition of Thieu-Ky-Khiem on the people of South Vietnam in order to insure their right to self-determination and so that all political prisoners can be released.

6. The Vietnamese pledge to form a provisional coalition government to organize democratic elections. All parties agree to respect the results of elections in which all South Vietnamese can participate freely without the presence of any foreign troops.

7. The South Vietnamese pledge to enter discussion of procedures to guarantee the safety and political freedom of those South Vietnamese who have collaborated with the U. S. or with U. S. -supported regimes.

8. The Americans and Vietnamese agree to respect the independence, peace and neutrality of Laos and Cambodia in accord with the 1954 and 1962 Geneva Conventions and not to interfere in the internal affairs of these two countries.

9. Upon these points of agreement, we pledge to end the war and resolve all other questions in the spirit of self-determination and mutual respect for the independence and political freedom of the people of Vietnam and the United States.

Pledge

By ratifying this agreement, we pledge to take whatever actions are appropriate to implement the terms of the People to people Treaty and to insure its acceptance by the government of the United States.

So there can be no doubt that Mr. Kerry met with the North Vietnamese and Vietcong delegation as a “negotiator,” which of course is illegal and seditious.

But that is what “smart, highly educated” people do, apparently.

Pingback: Today, John F. Kerry said, “It was easier,” during the Cold War. What he means is – it was easier – working against his country. | patrickcox488